Sometimes all it takes to alter the course of history is one pissed-off person. Supap Kirtsaeng wasn’t a crusader or lone nut; he was just an eBay trader who got backed into a legal corner and refused to give up.

To help pay for grad school at USC, he sold textbooks online—legitimate copies that he’d purchased overseas. But academic publishing behemoth John Wiley & Sons sued Supap, claiming that his trade in Wiley’s foreign-market textbooks constituted copyright infringement.

The implications were enormous. If publishers had the right to control resale of books that they printed and sold overseas, then it stood to reason that manufacturers could restrain trade in countless products—especially tech goods, most of which are made in Asia and contain copyrightable elements such as embedded software.

Intent on setting a precedent, Wiley slammed Supap with a $600,000 jury verdict and all but buried him on appeal. But the grad student hung tough, arguing that as lawful owner of the books he had the right to resell them. Eventually he convinced the US Supreme Court to grant review.

Once Supap’s struggle hit the spotlight, powerful supporters such as eBay, Public Knowledge, Costco, and Goodwill Industries joined the fray. But the forces pitted against Supap were arguably more powerful: the movie and music industries, publishers of books and software, and even the US Solicitor General.

Defying the odds, Supap won, and the case that bears his name has become a landmark.[1] But as the saying goes, “It ain’t over 'til it’s over.”

Throughout 2014, Congressman Bob Goodlatte, Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, has been holding hearings about copyright reform. Wiley and other prominent copyright holders have been pleading for legislative restrictions on Kirtsaeng.

On the other side, ownership interests want to ensure that Kirtsaeng applies to products with digital content. In September 2014, Congressman Blake Farenthold (R-TX) introduced a bill called “You Own Devices Act” (YODA) that allows owners of products with embedded software to transfer their rights.

Meanwhile Supap’s battle against Wiley continues to rage in court as the erstwhile eBay trader, now a mathematics professor in Thailand, seeks to recover millions in attorneys’ fees.

Dorm room to courtroom

Supap’s saga started with an idea for a dorm room sort of business. Since 1978, textbook prices in the US had soared by 700 percent, but the pricing wasn’t uniform worldwide. Publishers charged more in the affluent North American market and less in other regions. They called this practice “market segmentation,” but to many it seemed like price-gouging. Supap discovered this himself: a textbook priced at $50 overseas might cost $100 in the US.

Starting in 2006, Supap enlisted his family to make the rounds at Bangkok bookstores, buying titles like Organic Chemistry and Fundamentals of Physics. They shipped the textbooks to Supap’s apartment in LA, and he posted the books for sale on eBay.

Over the next two years Supap imported about 500 different titles and generated sales of around a million dollars. His profit of approximately $100K over the venture’s lifespan helped fund his school expenses.

But Supap didn’t take into account that Wiley might be watching. The Hoboken-based publisher, whose roots date back to a printing shop in Manhattan in 1807, was a publicly traded company (NYSE: JW.A) with annual revenue in excess of $1 billion.

In Wiley’s global empire, market segmentation was a revered practice. In the US market, Wiley sold premium-priced textbooks with glossy hard covers and sewn-ribbon bookmarks. In overseas markets, Wiley sold economy versions—the same content but with cheaper materials and a warning banner stating that the books couldn’t be sold in North America.

One of Wiley’s investigators, a “Senior Enforcement Specialist” named Patrick Murphy, uncovered Supap’s bookselling venture on eBay. Murphy contacted eBay, claimed that Wiley’s copyrights had been compromised, and obtained Supap’s personal information. In September 2008, Wiley’s outside counsel filed suit, accusing Supap of copyright infringement.

2 more images in gallery

Copyright's brick and mortar origins

In 1787, when delegates from the American colonies drafted the US Constitution, they included a provision called the Copyright Clause, empowering Congress to secure “for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” Congress exercised this power by passing the first Copyright Act of 1790.

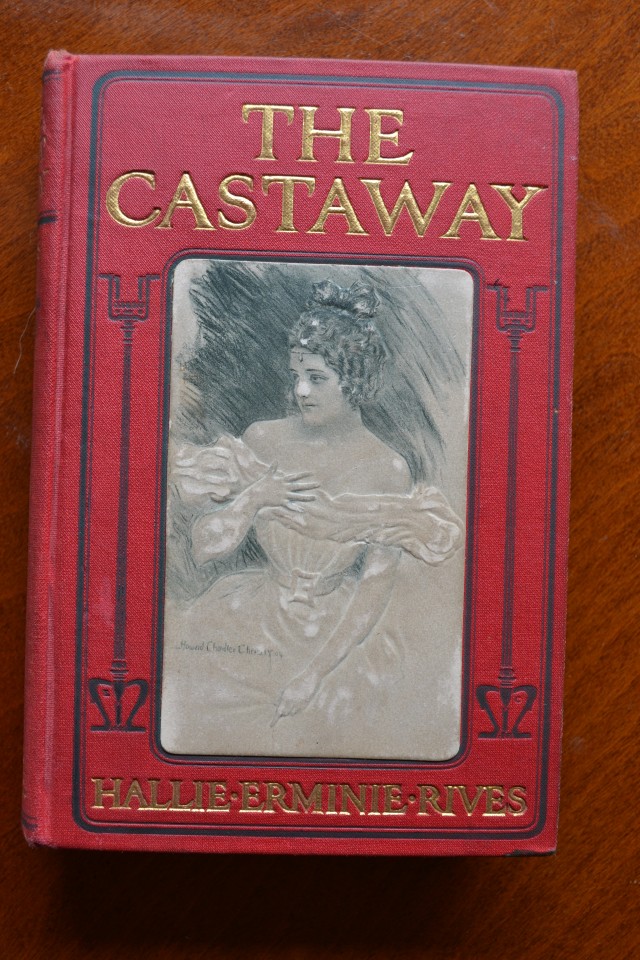

As time passed copyright holders pushed the limits of their rights. In 1904, Bobbs-Merrill Company published a novel, The Castaway, which included a statement that any sale of the book to retail customers for less than one dollar would constitute copyright infringement. But Isidor and Nathan Straus, co-owners of R.H. Macy & Co., bought a large quantity of the books and offered retail customers a price of 89 cents. Bobbs-Merrill sued them, and the case went up to the Supreme Court.

The justices found in favor of the brothers Straus, holding that when Bobbs-Merrill sold a given copy of The Castaway, its rights in that copy were exhausted. The buyer was free to turn around and “sell it again” at whatever price he wished.

The rule of Bobbs-Merrill v. Straus became known as the First Sale Doctrine and was incorporated by Congress into the Copyright Act of 1909. The First Sale Doctrine facilitated free exchange of copyrighted works. If a collector bought a painting and later wanted to donate it to a museum, she didn’t need the artist’s permission.

But as the decades passed, explosive growth of the publishing, film, and music industries gave copyright holders enormous clout. When Congress overhauled the law with the Copyright Act of 1976, the legislation granted the copyright holder exclusive control over importation and distribution of the copyrighted work. The legislation also restated the First Sale Doctrine, but it wasn’t clear how these competing provisions balanced out.

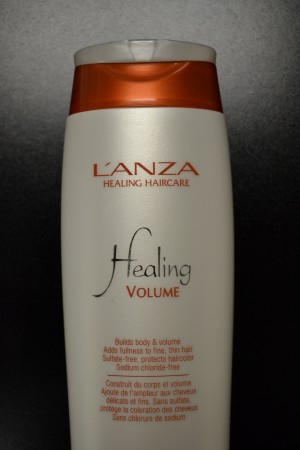

In 1998, a First Sale Doctrine case reached the Supreme Court. L’anza, a haircare products company, manufactured its products in the US but charged 30 to 40 percent less when selling overseas. Quality King Distributors, an independent or “gray market” distributor, started importing and reselling L’anza products in the US.L’anza sued Quality King, arguing that because its labels were copyright-protected, unauthorized importation violated its rights under the 1976 Act. Quality King countered that under the First Sale Doctrine, once L’anza sold the products it had no right to exercise downstream control.

The Supreme Court decided in favor of Quality King, holding that the First Sale Doctrine protected trade in “round-trip products”—copyrighted products made in the US, sold overseas, and brought back to the US. But in surplus language that lawyers refer to as “dicta,” the opinion by Justice John Paul Stevens suggested that the First Sale Doctrine would not apply to “copies that are lawfully made under the laws of another country.” The Quality King dicta called attention to the peculiar wording used by Congress in 1976 when it restated the First Sale Doctrine:

[T]he owner of a particular copy... lawfully made under this title..., is entitled, without the authority of the copyright owner, to sell or otherwise dispose of the possession of that copy.

Even though the dicta didn’t bind future courts, proponents of market segmentation argued fervently that, as suggested by Justice Stevens, in order to be “lawfully made under this title” a copyrighted work needed to be manufactured in the US. If the work was manufactured abroad it wasn’t made “under this title,” it was made under the laws of another country. Therefore, the First Sale Doctrine didn’t apply.

In 2004, the Swiss watchmaker Omega leveraged this argument into litigation against Costco. Omega charged premium pricing in the US for its popular “James Bond”-style Seamaster watches. Costco began sourcing Seamaster watches overseas, the upshot being that a buyer could get a Seamaster watch at Costco for $1,299 instead of paying $1,999 at an authorized Omega dealer.

Omega’s legal department devised a clever scheme: The watchmaker started engraving a tiny “Omega Globe” design on the back of Seamaster watches, waited for the watches to appear in Costco’s US stores, bought a pair of the watches, traced the serial numbers to prove that the watches had been sold overseas, and filed a lawsuit in Los Angeles accusing Costco of copyright infringement.

But the district judge soon ruled in favor of Costco’s argument that importation and resale of Omega Seamaster watches manufactured and sold overseas was protected by the First Sale Doctrine. Omega appealed to the Ninth Circuit, a court dubbed the “Hollywood Circuit” because of its reputed bias in favor of the entertainment industry.

On September 3, 2008, the Ninth Circuit reversed, holding that the First Sale Doctrine didn’t apply to foreign-made goods unless and until there was an authorized sale in the US. The timing was probably coincidental, but the following week, Wiley filed suit against Supap.

“More motivation”

With wire-rim glasses and swept-back gray hair, attorney William Dunnegan had a professorial visage, but when pursuing a suspected copyright infringer his manner was more scathing than scholarly. Supap first heard from Dunnegan’s firm when a process server appeared at the door of his LA apartment.

The soft-spoken grad student was taken aback. “If someone had explained Wiley’s position maybe I would have stopped,” he told Ars. But the surprise attack “gave me more motivation.”

Supap scraped together a retainer and hired Sam Israel, a streetwise native of Queens. An experienced copyright practitioner, Israel knew that the “winds were blowing against us” because of the Quality King dicta and the Ninth Circuit’s opinion in Omega v. Costco. But until the issue was squarely decided by the Supreme Court, whether the First Sale Doctrine applied to foreign-made goods remained an open question.

Dunnegan began pounding Israel with motions and other pretrial volleys. Although outmanned and outspent, the solo practitioner held his own... until the court dealt the defense a devastating blow.

In October 2009, Judge Donald Pogue, “persuaded by the dicta in Quality King,” ruled that Supap was precluded from relying on the First Sale Doctrine because it didn’t apply to foreign-made goods. His decision, although a model of academic analysis, failed to address the practical implications.

Thousands of products ranging from cars to computers were being manufactured abroad, and almost any creative element qualified for copyright protection. If Judge Pogue was right, then you might be the “owner” of a Japanese auto, Parisian painting, or made-in-China television set, but someone else controlled your right to sell, rent, gift, or donate it.

“bluechristine99”

On Tuesday, November 3, 2009, Judge Pogue convened a jury trial in his Manhattan courtroom. Although Supap had sold 500 different titles, many of them Wiley textbooks, to streamline the case Wiley focused on only eight titles. In his opening statement, Dunnegan told the jury that he’d prove three points: (1) Supap infringed Wiley’s copyrights in the eight titles, (2) the infringement was willful, and (3) Wiley should be awarded a large sum of “statutory damages”—a feature of copyright law allowing the copyright holder to recover up to $150,000 per willful infringement.

Deprived of the First Sale Doctrine as a defense, Israel hoped to convince the jury that even if Supap had infringed Wiley’s copyrights, he’d done so innocently. Israel’s opening statement emphasized that (1) Supap sold genuine Wiley textbooks, (2) Wiley profited from the sales, and (3) Supap had done research on Google Answers to confirm that reselling foreign-market textbooks was legal.

Wiley called as its first witness Patrick Murphy, the publisher’s in-house copyright enforcer. Murphy explained how he’d discovered Supap’s venture on eBay and ferreted out the information that led to the lawsuit. On cross-examination by Israel, Murphy admitted that Wiley had profited from Supap’s trade in foreign-market textbooks:

Israel: Just to be clear, every book that Mr. Kirtsaeng sold you made a profit?

Murphy: Wiley made a profit, correct.

For its next witness Wiley called Supap to the stand. Dunnegan cross-examined the grad student about the bookselling venture: how he sourced the books, how he resold them, and how much profit he made. Even though the lawsuit only focused on eight titles with total sales of $37,000, Judge Pogue allowed Dunnegan to elicit testimony that Supap’s overall venture had revenue of around a million dollars and profits of more than $100K.

Dunnegan focused especially on proving that Supap’s infringement was willful. He established that Supap knew about the warning banners:

Dunnegan: At the time you sold the book, did you also understand that the banner said it could not be exported from those certain areas of the world?

Supap: Yes, I understand that.

But the most damaging testimony came when Dunnegan cross-examined Supap about his eBay accounts. After eBay suspended Supap’s account because of his trading in foreign-market textbooks, he opened an account “bluechristine99” under his girlfriend’s name. Even after Wiley filed suit he’d continued doing business.

In his closing argument, Dunnegan painted Supap as a copyright scofflaw and urged the jury to return a verdict for $1.2 million in statutory damages. Israel countered that because there was no evidence that Wiley actually suffered a loss, the case shouldn’t be turned into a “million-dollar bonanza.”

On Wednesday morning, November 4, 2009, the jury began deliberating. Only 49 minutes later, they returned to Judge Pogue’s courtroom with a verdict against Supap for $600,000. Supap was astonished, explaining later that he never anticipated such a big number. “You know I’m a mathematician, so if something is not logical, why would I think that?”

All but defeated...

In January 2010, Wiley summoned Supap to a “debtor’s examination”—a deposition about the existence and location of his assets. By this time, Supap was nearly broke and had fallen months behind on his Ph.D dissertation. The beleaguered grad student endured hours of questioning about his car, his laptop, even his cell phone. At one point he begged for mercy, telling Dunnegan that “I want all this thing to stop. So I can focus on my study. So that I can finish and go back home...”

But Wiley applied even more pressure. Dunnegan convinced Judge Pogue to issue an order compelling Supap to surrender title to his golf clubs, and once his studies were completed, to turn over his computer and combination fax/printer/scanner.

Unbowed, Supap pressed forward with an appeal, funded by a loan from his father. Israel drafted a brief to the Second Circuit in New York, arguing that Judge Pogue had erred and that Supap had the right under the First Sale Doctrine to import and resell foreign-market textbooks.

Meanwhile, out in California, the fight arising from Costco’s trade in Seamaster watches hadn’t ended with the Ninth Circuit’s opinion in favor of Omega. In May 2009, Costco filed a petition asking the US Supreme Court to review the case.

Major players weighed in with amicus briefs, and in October 2009, the Supreme Court invited United States Solicitor General Elena Kagan to file a brief expressing the government’s views. In March 2010, the forces of market segmentation won another victory when the Solicitor General opined that the Ninth Circuit’s decision in favor of Omega was well-founded.

Meanwhile, Supap completed his long-overdue Ph.D. dissertation and flew home to Bangkok to teach mathematics at Silpakorn University. In April 2010, the Supreme Court granted Costco’s petition for review, setting the stage for a final decision about whether the First Sale Doctrine applied to foreign-made goods.

Then the plot took a twist: President Obama nominated Elena Kagan to the Supreme Court. The effect of this would soon become apparent.

In December 2010, the Supreme Court issued a cursory, unsigned decision in Costco v. Omega, stating that the justices were evenly divided 4-4. Justice Kagan had recused herself because she’d participated in the case as Solicitor General. Although the split decision had the effect of affirming the Ninth Circuit’s opinion, it didn’t establish binding precedent, so the question of whether the First Sale Doctrine applied to foreign-made goods remained open.

Suddenly all eyes turned to the Second Circuit, where Supap’s appeal remained under submission. Knowing that the case might reach the Supreme Court, the trio of appellate judges labored for months before announcing their decision. In the end, they split 2-1 in favor of Wiley.

Similar to the approach taken by Judge Pogue, the majority opinion aligned itself with the Quality King dicta. The opinion said little about possible adverse effects, stating that “if our decision leads to consequences that were not foreseen by Congress or which Congress now finds unpalatable, Congress is of course able to correct our judgment.”

But the third member of the Second Circuit’s appellate panel, Judge J. Garvan Murtha, dissented. He argued that market turmoil would result if copyright holders could restrain trade in foreign-made products. Also, granting enhanced rights to foreign-made products would encourage manufacturers to move their operations overseas.

Although Judge Murtha’s dissent provided Supap with a glimmer of hope, the outlook remained dim. He’d lost at trial. He’d lost the appeal. In Costco v. Omega, four justices of the Supreme Court had decided that the First Sale Doctrine didn’t apply to foreign-made goods, and Justice Kagan, while Solicitor General, also endorsed this position. And even if Supap was inclined to continue the fight, he lacked the wherewithal to keep paying attorneys’ fees.

It was at this point, when Supap appeared all but defeated, that another lawyer stepped forward and volunteered to help.

A new face

Joshua Rosenkranz was on a roll. A brilliant appellate advocate, he’d won a string of high-profile cases and was about to be named litigator of the year by American Lawyer magazine.

Rosenkranz knew that billions of dollars in commerce hinged on the outcome of the battle over the First Sale Doctrine and that price-gouging could result if Wiley won. Youthful despite his mane of gray hair, and with a fondness for underdogs, Rosenkranz was eager to fight back against the forces of market segmentation.

“It was hugely consequential,” he told Ars. “Everyone thought we were going to lose.”

Offering his services pro bono, Rosenkranz joined forces with Israel and filed a petition on behalf of Supap seeking review in the Supreme Court. In April 2012, the Supreme Court granted the petition. Supap’s once-obscure legal ordeal had morphed into one of the highest-stakes copyright cases in US history.

In deciding how to position the case, Rosenkranz and Israel faced a tough decision. The language in the 1976 Act stating that the First Sale Doctrine applied to copies “lawfully made under this title” could be read various ways. How should they argue the point?

Rosenkranz believed that Congress’ intent was to focus on lawfulness of manufacture, not location of manufacture. He favored a simple interpretation: “lawfully made under this title” meant made in accordance with this title no matter where the item was manufactured.

The problem was that the Supreme Court in Quality King suggested that the First Sale Doctrine didn’t apply to foreign-made goods. Rosenkranz knew that the justices were loath to contradict themselves, even if the prior pronouncement was non-binding dicta.

But Rosenkranz believed that “victory would go to the side that had the simplest reading.” He decided that if asked the question point-blank, he’d answer that the Quality King dicta had been wrong.

Meanwhile, despite the successes that Dunnegan achieved, Wiley decided that the case warranted an appellate specialist. The publisher engaged Theodore Olson, the lawyer who’d successfully argued the presidential election-deciding case of Bush v. Gore.

Powerful interests from across the nation began lining up on both sides, engaging top law firms to prepare amicus briefs. It was truly a clash of the titans: in Wiley’s corner the Motion Picture Association of America, Recording Industry Association of America, Business Software Alliance, Association of American Publishers, American Bar Association—the list goes on.

But Supap’s corner had its own behemoths: eBay, Google, and organizations representing hundreds of technology companies, the Retail Industry Leaders Association, the Entertainment Merchants Association, Public Knowledge—again the list goes on. Supap’s side also garnered support from the nonprofit world: The American Library Association, Goodwill Industries, the Association of Art Museum Directors, and many others.

The Owners’ Rights Initiative, an advocacy group headed by Washington lobbyist Andrew Shore, launched a public relations campaign around the slogan, “You Bought It, You Own It (you have a RIGHT to resell it!).” The New York Times sided with Wiley, but much of the spin was along the lines of Jennifer Waters’ blog in MarketWatch, where she warned: “Your right to sell your own stuff is in peril.”

On argument day, Monday, October 29, 2012, even Mother Nature weighed in.

“To put it bluntly, yes.”

With Hurricane Sandy bearing down on the city, most of official Washington had closed its doors. But Rosenkranz, convinced that the Supreme Court would sit, awoke at 4am and began reviewing his top-hundred flash cards.

At a quarter to nine Rosenkranz and his opponent, Ted Olson, arrived at the Supreme Court and stepped out of their respective taxis. The doors to the courthouse remained open.

An argument before the nation’s highest court is like walking through a minefield—every step is fraught with peril. Soon after Rosenkranz launched into his well-rehearsed presentation Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg interrupted him:

Justice Ginsburg: But your reading…is essentially, once a copy is sold anywhere, the copyright owner loses control everywhere. That is essentially your argument.

Rosenkranz: That is correct, Your Honor.

Justice Ginsburg: [T]hat has been called, I think, the universal exhaustion principle.

Rosenkranz: International exhaustion. Yes, Your Honor.

Justice Ginsburg: And we are told that no country has adopted that international exhaustion regime…

Rosenkranz knew that this was an inopportune beginning, focusing on whether the rule he advocated would turn the United States into a copyright profligate. But he stuck to his position, parrying questions until Justice Antonin Scalia steered the argument in another direction:

Justice Scalia: Do you mean by “lawfully made under this title,” simply lawfully made in a manner that does not violate United States copyright law?

Rosenkranz recognized the question as a trap and quickly answered, “No, Your Honor.” If he’d answered “yes” then he would’ve walked headlong into the principle that US law doesn’t apply overseas. Instead, he argued that the statute meant in accordance with the standards articulated in US copyright law. His argument gained steam when Justice Elena Kagan jumped in:

Justice Kagan: So, Mr. Rosenkranz… is your theory of this statute essentially that this language means non-piratical copies as that is defined by US copyright law?

Rosenkranz: Yes, Your Honor...

As the exchange continued, Rosenkranz grew more confident. When Justice Sonia Sotomayor began inquiring, her questions allowed Rosenkranz to reiterate his key point:

Rosenkranz: [W]e are not focusing on whether the making was under this title; we’re focusing on whether it was lawful under this title.

Justice Stephen Breyer waded into the mix, rephrasing the argument in a manner that Rosenkranz liked:

Justice Breyer: [E]ither it was manufactured directly and received an American copyright, or… it was manufactured in a way that satisfied the conditions of the American statute….

Rosenkranz: Yes, Your Honor.

But Justice Ginsburg struck back, suggesting that Congress intended to give copyright holders the ability to engage in market segmentation. Rosenkranz resisted, arguing that when Congress revamped the law in 1976, “not a word was uttered about dividing distribution or divided markets.”

Then came the moment of truth, the question that Rosenkranz had anticipated but that still made him sweat:

Justice Kagan: Mr. Rosenkranz, there is that passage in Quality King, which is, I think it’s fair to say, unfortunate to your position. Is your basic view of that passage that it was simply ill-considered dicta that we should ignore?

Rosenkranz: To put it bluntly, yes….

He’d gone and said it: The Supreme Court should disregard a statement in one of its own opinions and instead adopt his interpretation. It was a bold position, but when Rosenkranz returned to his seat he felt that the justices “weren’t beating the living daylights out of me.”

Parade of horribles

Ted Olson stepped to the podium on behalf of Wiley and launched into an argument that Congress had amended the copyright law in 1976 in part to stop unauthorized importation of copyrighted works. Soon he began facing questions that put him on the defensive:

Justice Breyer: Now, under your reading…the millions of Americans who buy Toyotas could not resell them without getting the permission of the copyright holder of every item in that car which is copyrighted.

Olson seemed to have difficulty with the question, answering “that is not this case.” Justice Breyer continued to press:

Justice Breyer: Now, explain to me, because there are… millions of dollars’ worth of items with copyrighted indications of some kind in them that we import every year; libraries with three hundred million books bought from foreign publishers…; museums that buy Picassos… and they can’t display it without getting permission from the five heirs who are disputing ownership of the Picasso copyrights….

Again Olson tried to deflect the question, arguing that “we’re not talking about this case…” But Justice Anthony Kennedy wasn’t satisfied.

Justice Kennedy: You’re aware of the fact that if we write an opinion… with the rule that you propose, that we should, as a matter of common sense, ask about the consequences of that rule.

Olson countered that the “parade of horribles” was exaggerated. Justice Breyer observed wryly that “[s]ometimes horribles don’t occur because no one can believe it.” By the time Olson returned to his seat, Rosenkranz and Israel realized that Wiley’s case might be foundering.

Deputy US Solicitor General Malcolm Stewart offered the Court a compromise position, contending that the 1976 Act prohibited unauthorized importation of foreign-made goods, but once the goods were lawfully sold in the US, any subsequent sales would be protected by the First Sale Doctrine. This argument seemed to fall flat:

Chief Justice Roberts: That’s an awfully difficult maze for somebody… to get through….

Toward the end there came a moment rarely seen in arguments before the Supreme Court—an admission that changes the tenor of the case:

Justice Alito: Which of the following is worse: All of the horribles that [Kirtsaeng] outlines to the extent they are realistic, or the frustration of market segmentation, to the extent that would occur, if [Kirtsaeng]’s position were accepted?

Stewart: Well, if they actually happened, then I think the horribles would be worse….

Even after this concession by the government, Rosenkranz still didn’t feel confident. “I’m the guy who lies awake worrying about all the ways we could lose the case.”

The final decision

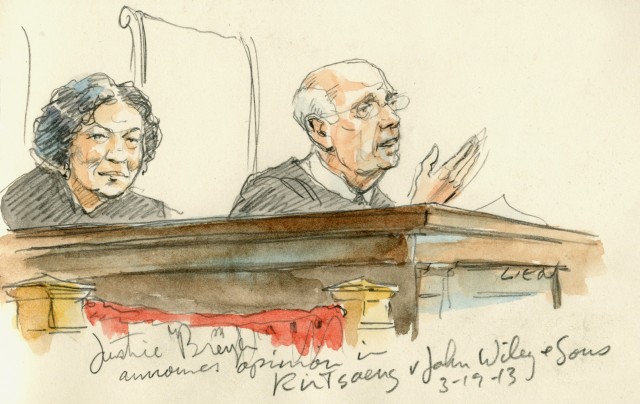

On Tuesday, March 19, 2013, Dr. Supap Kirtsaeng was meeting with his colleagues at Silpakorn University when his cell phone started ringing. Excusing himself he ran to his office, checked the Internet, and “almost yelled” with excitement.

The vote was 6-3 in Supap’s favor. With Justice Breyer authoring the majority opinion, the Court decided that the phrase “lawfully made under this title” wasn’t intended by Congress to impose a “geographical limitation.” Regarding market segmentation, the Court found no support for the notion that copyright “should include a right to divide markets or… to charge different purchasers different prices for the same book…”

Justice Ginsburg, perhaps the Court’s most liberal member, wrote a dissent joined in by two conservatives, Justices Kennedy and Scalia. Elena Kagan, who as Solicitor General had signed the opinion favoring Omega, as a Supreme Court justice changed her mind and sided with Supap.

As analysts and bloggers weighed in, Justice Breyer’s decision garnered widespread praise. Even the Los Angeles Times, hometown newspaper of the entertainment industry, hailed the result. It stated that courts “have to balance copyright holders’ interests against the public’s ability to access those works and exercise the rights of ownership.”

The fight isn’t over. Tension between owners and copyright holders, as old as the copyright law itself, continues to simmer. The House Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property and the Internet has been holding hearings on copyright reform. At a June 2, 2014, field hearing in New York, rights holders and owners traded jabs about Kirtsaeng and the proper scope of the First Sale Doctrine. Disagreement also surfaced in a November 14, 2014 hearing about copyright issues in education.

Andrew Shore from Owner’s Rights Initiative thinks that the ruling is safe. “Kirtsaeng was the right decision and I don’t think Congress will tamper with it,” he posits. “The issue now is digital content.”

With embedded software now found in countless products ranging from cars to clocks, the question becomes whether rights in these products will be controlled by the owners or by copyright holders. Cisco’s “Internet of Everything” initiative makes the point that the physical world is increasingly blending into the digital world, but Shore sees peril in this trend. "We have to ask ourselves: do we want to be an ownership society or a licensing society?”

On September 18, 2014, Congressman Blake Farenthold (R-TX) introduced the “You Own Devices Act” (YODA), which would expand ownership rights in technology products by allowing users to transfer the rights to software inside the devices. “This straightforward and tightly focused bill reinforces our First Sale rights and preserves our ability to truly own the products that we buy,” said Farenthold in a statement.

YODA won immediate support from consumer rights groups and a surprise endorsement from the LA Times. Farenthold is reportedly seeking bipartisan co-sponsorship for YODA and plans to reintroduce the bill in the 114th Congress.

Meanwhile Supap and his lawyers are still battling Wiley. In December 2013, Judge Pogue denied his motion for attorneys’ fees. As of November 2014, the one-time eBay bookseller, still represented by Israel, is moving forward with yet another appeal.

Doug Kari is a lawyer, business executive, and freelance writer in Southern California.

[1] Full disclosure: the author wrote an amicus brief in support of Supap’s position that was cited by the Supreme Court in its decision.